We get a lot of mail at NPR Music, and amid the detergent sampler that broke and spewed suds all over our mortgage bill is a slew of smart questions about how music fits into our lives — and, this week, what makes a successful solo album.

Rick Simineo writes via Facebook: "Can you talk us through the right and wrong way of doing a solo album after time in a band, along with some examples of each?"

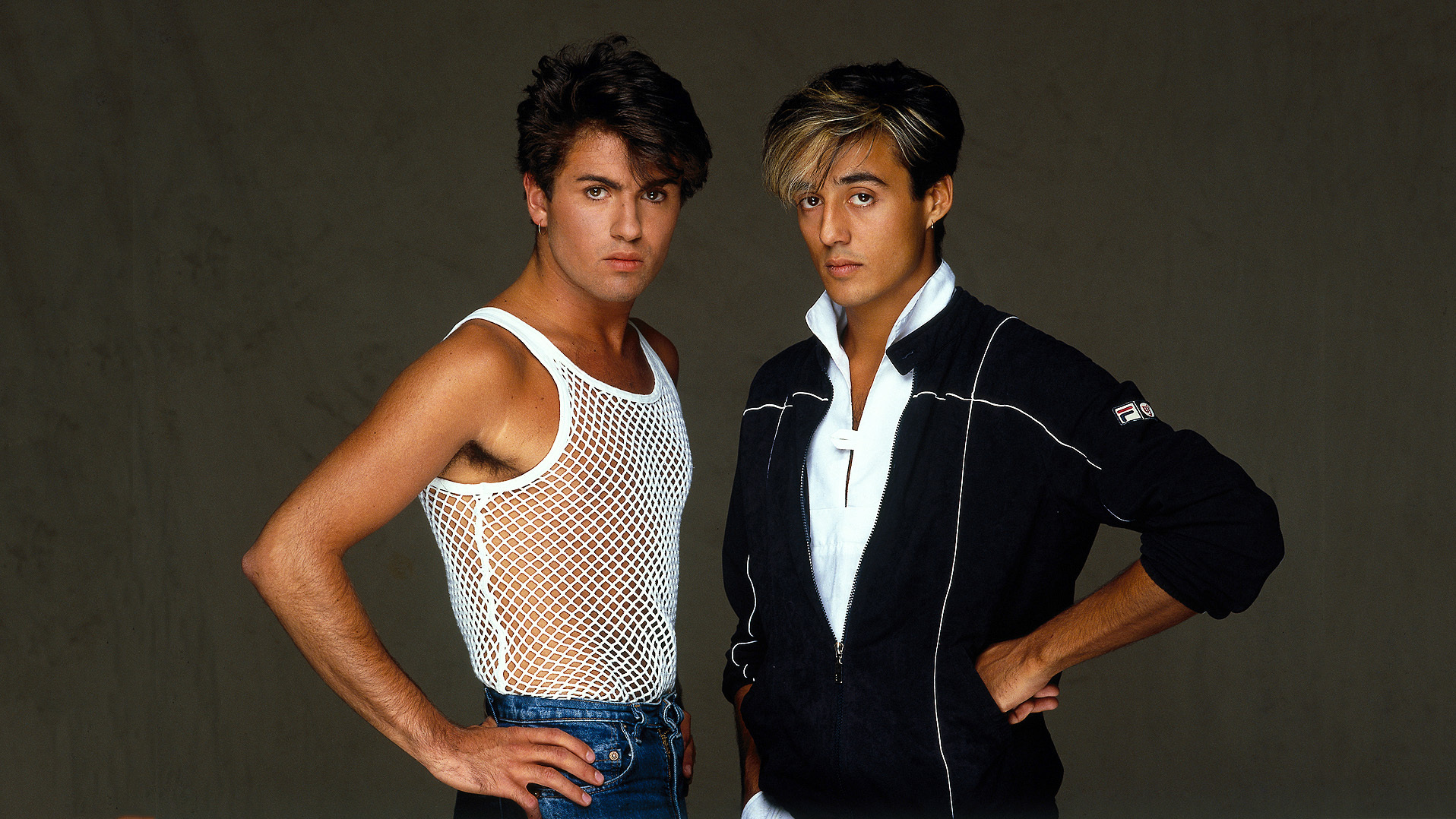

George Michael (left) and Andrew Ridgeley both went solo after Wham! broke up. One fared just a little better than the other.

Brian Aris

There's no one unifying principle behind solo success — it's been done both right and wrong in a hundred different ways, for a thousand different reasons — but I've tried to puzzle out a few guidelines based on the examples that spring to mind. For the sake of something approximating brevity, I'm going to stick to singers, because they're the ones most likely to launch high-profile solo careers.

So many of the successful singer-goes-solo stories that jump to my mind are cases in which the newly minted solo artist has a persona that needn't be confined or constrained; in which the mystique and allure of the singer has always dwarfed that of the performers around him or her. In The Smiths, Morrissey benefited immeasurably from Johnny Marr's guitars, but if you cared about The Smiths, you knew exactly what Morrissey was all about long before he became a solo artist. Bjork made a bunch of big records with The Sugarcubes, as did Natalie Merchant with 10,000 Maniacs, as did Gwen Stefani with No Doubt, but no one boggled at the cognitive dissonance between their solo and band work. In short, it helps to be the iconic face of a band if you're trying to become an iconic solo singer — but even that's no sure thing, if the uneven solo careers of Mick Jagger and Debbie Harry are any indication.

The next rule is to evolve gradually. George Michael wasn't exactly a brooding artiste in Wham!, and his hugely successful early solo records meet at the midpoint between his bubblegum persona and the more "adult" side (in several senses of the word) he'd explore later. Sting's post-Police album The Dream of the Blue Turtles finds a similar comfort zone between fizziness and mopery; it took a few years for the singer's adult-contemporary side to dominate completely. Justin Timberlake found a path from boy-band stardom in 'N Sync to solo stardom by locating the midpoint between his old group and sexy soul. Though there are cases in which hairpin turns have worked for people — Mike Patton leaving Faith No More and forming the inscrutably spastic oddity Mr. Bungle, for example — some performers have been viewed as unbearably self-indulgent once liberated from the bands that once contained them. (David Lee Roth was a huge solo star for a few years after leaving Van Halen, but the schtickiness of it all produced rapidly diminishing returns.)

To me, the most intriguing solo breakouts occur in bands with multiple competing — and often contradictory — visions. Bands often contain several highly individual songwriters, and so it's intriguing to watch a family tree emerge from the roots of an Uncle Tupelo (Wilco's Jeff Tweedy, Son Volt's Jay Farrar), a Velvet Underground (Lou Reed, John Cale, et al), a Fleetwood Mac (Stevie Nicks, Lindsey Buckingham, Christine McVie), a Beatles (all four of 'em), a Fugees (Lauryn Hill, Wyclef Jean, Pras), a Hüsker Dü (Bob Mould, Grant Hart), and even an Eagles (Glenn Frey, Don Henley, et al). That individual work can often be informed by the exhilaration of liberation, but it also comes with fascinating amounts of pressure: When a band breaks up and everyone goes solo, history will often judge its legacy by which solo act fares best. The roles of Kelly Rowland and Michelle Williams in Destiny's Child, for example, will always be viewed through the lens of Beyonce's subsequent success. In most cases, that battle is won by who's got the strongest songs out of the gate.

Finally, it really helps to go solo at the right time — to not wait until a band has started to decline before striking out on your own. Several new solo albums have crossed my desk recently that might have experienced a huge profile had they been released 10 or 15 or 20 years ago: Live's Ed Kowalczyk, Collective Soul's Ed Roland, Creed's Scott Stapp. But for those guys, going solo now means rebranding themselves and bearing the weight of their bands' respective legacies. Of course, it holds true for solo acts — just as it holds true for bands — that most musicians come with commercial expiration dates, no matter how many smart moves they've made along the way.

[Incidentally, yes, about 14 zillion examples aren't included in this thumbnail sketch: Iggy Pop, assorted Jacksons, Diana Ross, Kenny Loggins, Robert Plant, Gloria Estefan, Paul Simon, Peter Gabriel and Phil Collins, Glen Hansard, Billy Idol, Rob Thomas, a couple Black Eyed Peas, and on and on. Please feel free to bring 'em up and have at it in the comments.]

Got a music-related question you want answered? Leave it in the comments, drop us an email at allsongs@npr.org or tweet @allsongs.

from Digg Top Stories http://www.npr.org/blogs/allsongs/2013/11/08/243950702/the-good-listener-the-right-and-wrong-way-to-go-solo?ft=1&f=

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire